By Jodi Stemler

Title image: A hunter sets a turkey decoy. Photo courtesy USFWS/NEAFWA. For more information on the turkey restoration data discussed in this story, see the fact sheet Wild Turkey Population Restoration, and read the original analysis via Southwick Associates.

This holiday season, I’ll be traveling through the airport with a frozen wild turkey in a YETI Hopper as my carry-on. It’s a tradition we started about five years ago, and I’m always proud to supply a key portion of my family’s annual Thanksgiving dinner—though the comments from the TSA Agents can be amusing.

Turkey and Thanksgiving have gone hand in hand since colonial times, right? Not exactly… the well-known tale of the decimation of wildlife followed by the restoration and return to huntable populations is no more evident than it is with wild turkeys. On the front end of that restoration effort was the New York State Department of Environmental Conservation, with help from funding through the Pittman-Robertson Federal Aid in Wildlife Restoration Fund. New research is showing how that initial investment is paying big dividends, and how having wild turkey on the Thanksgiving table is now something we can all celebrate.

From Abundant to Scarce

Despite popular belief, historians aren’t clear whether turkeys were on the table at the first Thanksgiving dinner shared by colonists and the Native Americans in 1621. Wild turkeys were abundant throughout the colonies, and Governor William Bradford of the Plymouth Colony wrote of the “great store of wild turkeys, of which they took many.” He also notes before that storied first Thanksgiving the Englishmen went on a successful “fowling” mission, though waterfowl might have been a more likely quarry during the fall migration. Instead, the Wampanoag tribe brought several deer to the dinner, so venison was probably the primary protein.

In truth, by the time that President Abraham Lincoln issued a proclamation in 1863 declaring an official Thanksgiving holiday to occur in late November, wild turkeys were largely extirpated across much of the country. The once prolific birds fell victim to unregulated harvest by market hunters and the conversion of forested habitat to farmland. As an example, by the late 1800s about 75% of New York state was cleared for farmland and turkeys are believed to have been gone from the state since the 1840s. By 1920, wild turkeys were lost from 18 of the original 39 states in its historical range.

In the late 1880s, states began to regulate the take of game species; Pennsylvania first regulated turkey hunting in 1873 and New York hired eight “Game Protectors” in 1880 to police the woods and waters of the state. Controlling illegal harvest continued to be a challenge, but as farming declined abandoned farms transitioned through successional stages to brush and eventually woodlands. Habitat was back and around 1948—a century after they were eliminated from the state—wild turkeys from a small remnant population in Pennsylvania moved into western New York.

Bringing Back the Birds

Turkeys were back in New York, but there was still a lot of work to do. Those intrepid birds that had wandered into the state found plenty of habitat and were expanding rapidly, but they could only go so far. Game managers decided to help them along and in 1952 they began to raise turkeys in a game farm to reintroduce in the wild, stocking over 3,000 pen-raised birds over the next eight years. But the captive-reared birds weren’t wily enough to avoid predation and their natural reproduction was low, so the populations failed.

In 1959, Department of Environmental Conservation biologist Fred Evans pioneered a method to capture wild turkeys from the booming populations in Allegany State Park. During winter when food sources were not as abundant, the team would lure birds into an area using corn or other grains. When there was a large enough group of turkeys, a net was shot over the top of them; biologists would place the birds in crates and translocate them to other areas of the state with suitable unoccupied habitat. According to a NYSDEC history document, “A typical release consisted of 8 to 10 females and 4 to 5 males. These birds would form the nucleus of a new flock and generally were all that was necessary to establish a local population.”

Since those early trapping efforts in the late 1950s until the early 1990s, 1,400 turkeys were moved within New York and helped reestablish wild populations across the state. New York also sent more than 300 wild turkeys to the states of Vermont, Massachusetts, New Hampshire, New Jersey, Connecticut, Minnesota, Rhode Island, Delaware, and the Province of Ontario, helping to reestablish populations throughout the Northeast. Similar translocations were carried out by states across the country, often working with partner groups like the National Wild Turkey Federation.

Restoration Returns

Like many other states, New York’s turkey restoration efforts—starting with the early game farms through the trap and translocation of wild birds—were funded in large part through the Pittman-Robertson Federal Aid in Wildlife Restoration Fund. Enacted in 1937, this program redirects a portion of a federal excise tax on firearms, ammunition, and archery equipment for use by state fish and wildlife agencies to conserve wildlife populations. Those federal grant funds, paid by the shooting sports industry and the consumers that buy these products, are matched by the states using hunting license revenues. It’s a public/private partnership, bankrolled largely by hunters and recreational shooters but it’s clearly paying dividends and wild turkeys are just one example.

According to Mike Schiavone, game management section head in the NYSDEC division of wildlife, “Funding through the Pittman-Robertson Wildlife Restoration program clearly changed the face of wildlife conservation. Wild turkey restoration in our state is directly connected to the dedicated funding through this program and hunting license fees that was made available to restore and manage this popular game bird.”

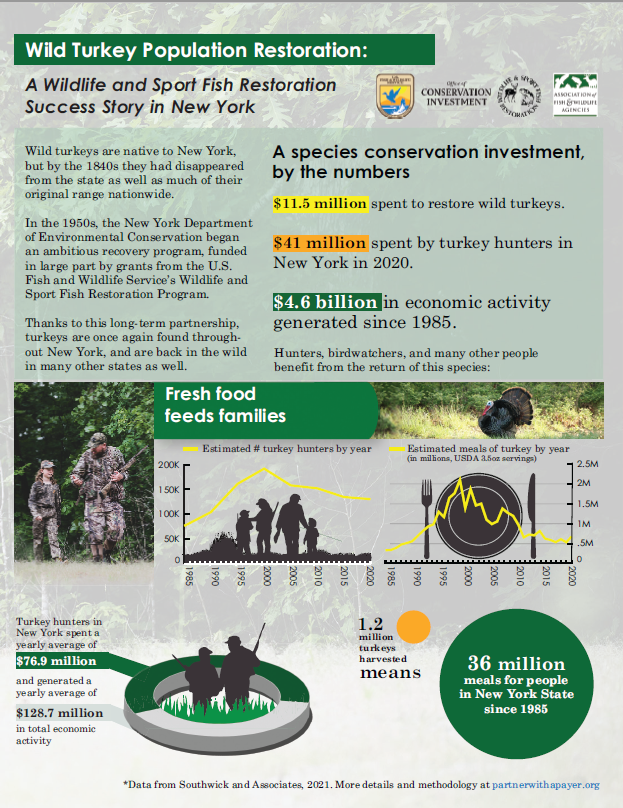

Natural resource economics firm Southwick Associates recently took a closer look at how that investment of Pittman-Robertson (P-R) funds worked for wild turkeys in New York. The state devoted a total of $2.7 million dollars (worth $11.5 million in 2020 dollars) of total grant funding to turkey restoration in New York from 1953-1985. They spent an annual average of $348,095 through this time and the turkey population rebounded. Ever since the state re-opened turkey hunting seasons, the ripple effect to the state’s economy has been growing.

In total, $4.6 billion of economic activity has been generated by turkey hunting in New York from 1985-2020. This activity includes direct expenditures by turkey hunters and the additional rounds of spending that occur as hunters’ dollars move through the economy. As an example, turkey hunting supports 555 jobs in New York, from hunting supply stores, local motels, and restaurants to businesses statewide. Turkey hunters have been spending on average $76.9 million annually since 1985, which in turn generates an average of $128.7 million of economic activity each year. This means more than 10 times the total grant funding from 1953-1985 is generated each year because of turkey hunting.

“It’s not often that a relatively small investment creates such a significant business opportunity. Too often people think that conservation comes at the expense of commerce, but we continue to find that this is not the case,” noted Rob Southwick. “Although many Americans don’t ever see wild turkeys, these birds still have a significant impact on state economies, even in urban areas. And it isn’t just turkeys—P-R funds have helped restore deer, elk, and waterfowl that also have tremendous economic impacts.”

These funds, coming through the firearms and archery industries, serve as the foundation for wildlife conservation efforts—but the restoration successes undertaken in the latter part of the 20th century are now critically important to economies across the country. And it’s a self-perpetuating boon. Fully restored turkey populations resulted in the rapid growth of turkey hunting in New York and many other states, and with a dramatic increase in the sale of hunting licenses and the development of turkey hunting products—many of which carry that small excise tax that goes right back to the states to continue wildlife conservation and management activities.

As Becky Humphries, CEO of the National Wild Turkey Federation notes, “We often see that turkey hunting is a portal, an entry into the hunting and shooting sports. Because the populations are so strong, there is a lot of interest in hunting them and plenty of opportunities to get out. But they are a wily species, and you have to learn about the bird and their behavior to be successful. This builds skill as a hunter and helps develop hunting ethics and safety.”

But the other thing that is attracting people to turkey hunting, says Humphries, is how wonderful they are as table fare.

Bringing Home the… Turkey

Which brings us back to the beginning of this story and wild turkeys on the Thanksgiving table. These are naturally organic, free range animals and wild turkey is higher in protein and lower in fat than store bought turkeys. According to NYSDEC harvest information, 1,213,654 turkeys have been harvested in spring and fall turkey seasons in New York since 1985—at about 6.5 pounds of edible meat per bird and using the USDA standard serving size of 3.5 ounces, that’s over 36 million servings of wild turkey! The 2020 harvest in New York was 23,714 birds providing about 705,000 servings, which is equivalent to feeding just under half the population of the Bronx. While New York is consistently on the higher end of total turkey harvest, it’s clear that wild turkeys are feeding a lot of people every year.

And, of course, there is that tremendous sense of pride and a connection to your food when you serve on your Thanksgiving table the turkey that you hunted. Which is why I will once again be lugging my bird through the airport this year.

To those of us enjoying a meal of wild turkeys on the holiday table, we give thanks to the men and women of conservation that helped bring back these incredible native birds. And to those of you who would like to do so next year, I can guarantee that NWTF or your state fish and wildlife agency will be teaching a turkey hunting class near you—and you becoming a hunter will continue this incredible cycle of conservation.

Fact Sheet: A Species Conservation Investment, By the Numbers