This article originally appeared in the Shooting Industry Magazine.

By Craig Springer, USFWS

Ohioan Joseph List may have lived his adult life without ever seeing a white-tailed deer. This first-generation American born in 1860, experienced the spring of life during the Civil War. This son of German immigrants was Everyman from Anytown, USA — and he was a hunter.

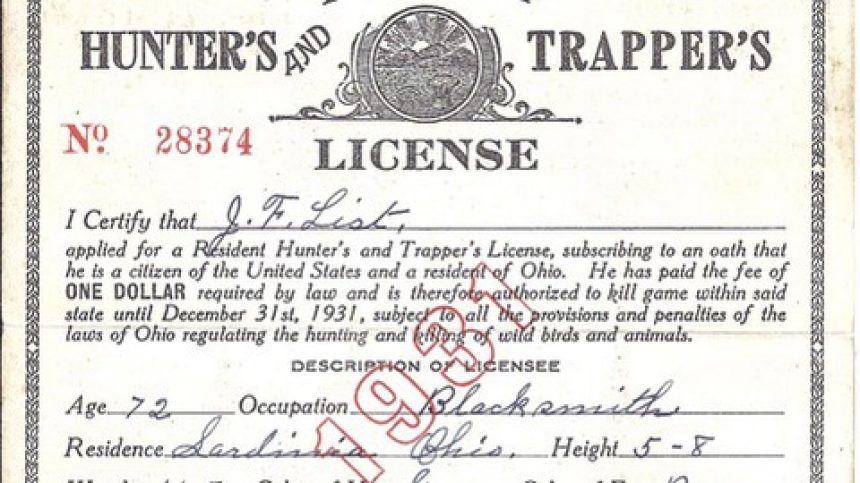

List made a living as a blacksmith in Sardinia, so notes his 1931 Ohio Department of Agriculture hunter’s and trapper’s license. It cost him $1 for the privilege to harvest game and furbearer pelts. He was 72 when he laid his signature down. The faded ink and feathered edges of the linen paper mark the passage of nine decades. The crease shows he likely wore it on the back of his hunting coat so that conservation officers could easily check it.

Two Lines Tell a Bigger Story

The hunting proclamation that List carried in his coat speaks to prevailing conditions that would soon lead to landmark conservation legislation, the passage of the Pittman-Robertson Act, then six years away. Its soiled pages of heavy card stock show he thumbed it a time or two. Wild turkey is not mentioned in the proclamation given they no longer existed in Ohio. Two lines stand out.

Deer: Protected

Ruffed grouse: Protected.

By the time of List’s birth, whitetail numbers had severely declined — range wide. Unregulated subsistence and market harvest coupled with habitat loss eventually made whitetails a rarity. The Civil War influenced wildlife where List lived.

The hilly Appalachian Piedmont of southern Ohio proved important in saving the Union. The area produced vast amounts of iron for bayonets, cannons, and kettles. Place names like Ironton and Buckeye Furnace tell of a precinct in military and conservation history. The smelters required two things, iron ore and wood. They converted red maple, white oak, and yellow pine into molten dusky metal leaving an ever-expanding denuded forest.

By 1900, little of Ohio’s mosaic woodlands remained. Deer were decimated.

Conditions List witnessed in 1931 were emblematic of prevailing circumstances over much of America. Elk were nearly a thing of the past in the West — and had long been extirpated in the East. Pronghorn skittered over the prairies no more.

While List was the Everyman, fellow Ohioan Carl Shoemaker was a man of uncommon abilities, and he too was a hunter. Born in 1882, Shoemaker came of age near Lake Erie. He earned law degree at Ohio State and wended west to Roseburg, Ore., where he published the Evening News. His interest in politics and conservation converged with an appointment in 1915 to lead the Oregon Fish and Game Commission. In 1930, Shoemaker turned east and hired on with the U.S. Senate Special Committee on Conservation and Wildlife Resources.

An Immediate Impact

Seven years later, Shoemaker crafted the Pittman-Robertson Act to redirect an existing federal 10% excise tax on firearms and ammunition to pay for the conservation of birds and mammals. The proposed law fell to an agriculture committee chaired by Representative Scott Lucas of Illinois to move the bill along. But Lucas stalled.

Then a curious thing happened. Shoemaker urged women’s groups and garden clubs of Illinois, a large force of 80,000 women in 1,075 clubs, to cajole the representative in reporting the bill out of committee. The campaign worked, Lucas told Shoemaker so.

Pittman-Robertson became law in September 1937, codifying an industry-state-federal partnership that continues to provide reliable and consistent funding to state fish and wildlife agencies. Within a year, 43 of 48 state legislatures protected hunting license receipts from use outside of conservation. Pittman-Robertson dollar and license fees were explicitly reserved for land acquisition, habitat improvement, and scientific research all directed at wildlife restoration.

In 1938, Ohio landed $39,017 in Pittman-Robertson funding. Five years later Ohio held its first deer season since 1900 in three counties lasting three days.

In 1950, nearly half of Ohio’s 88 counties hosted a three-day-long deer season where hunters harvested 4,000 whitetails. In August, coming off the astounding success of Pittman-Robertson, President Truman signed the Dingell-Johnson Act (aka Sport Fish Restoration) into law to similarly fund fisheries management, research and angler and boater access via federal excise taxes on fishing tackle, paid by the manufacturers.

235,000 Whitetails & Climbing

Joseph List left his earthly domain nearly two months later, passing away in late Sept. 1950. He outlived eight of his 13 children and witnessed an astounding number of events in his 90 years. One would hope that included a buck deer on the edge of a southern Ohio meadow on an autumn morning—in his time, surely an uncommon sight.

Today, Ohio’s deer season opens in September and runs into February. As of mid-January 28, 2025, more than 235,000 whitetails have been harvested with firearms, bows and crossbows across the state. The Ohio Division of Wildlife received in 2025, $17.7 million in Pittman-Robertson funds.