This article originally appeared in the Fishing Wire on April 14, 2022.

By Paul Rauch

The 87th North American Wildlife and Natural Resources Conference sponsored by the Wildlife Management Institute convened last month in Spokane, Washington. The annual event draws wildlife professionals from all corners—biologists and administrators employed in state fish and wildlife agencies, and representatives from federal natural resources agencies including my colleagues from the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service’s Wildlife and Sport Fish Restoration program.

Business interests are well represented at the conference through the attendance of trade organizations. The National Shooting Sports Foundation represents the firearms and ammunitions manufacturers; the Archery Trade Association speaks for the bow manufacturers; the American Sportfishing Association concerns itself with those who make fishing tackle.

These organizations speak for businesses large and small, many of whom pay excise taxes on their manufactured goods that fund fish and wildlife conservation. They have been at it since 1937, paying a 10- to 11-percent tax on select products since the passing of the Federal Aid in Wildlife Restoration act, or Pittman-Robertson in common parlance. Fishing tackle was added to the mix in 1950 at the passage of the Federal Aid in Sport Fish Restoration, or Dingell-Johnson. Together the two laws coupled with fishing, hunting, and trapping license sales comprise the foundation of the American system of conservation funding, an arrangement that stands beyond compare.

This gives me some pause for reflection. I have the published proceedings of the first conference that occurred over a cold, snowy four days in February 1936, in Washington, D.C. The proceedings—a 675-page tome—is wrapped in beige hardbound cloth without ornamentation. The U.S. Senate’s Special Committee on Conservation of Wildlife Resources chaired by Key Pittman of Nevada published the book, overseen by the committee’s secretary, Carl Shoemaker. The contents between the covers are hardly plain.

The book’s third leaf portends today’s triad of industry, state fish and wildlife agencies, and the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service that together make things go—for fishing, hunting, and boating. There, you read an order from President Franklin Roosevelt that by calling the conference; it is his desire to see “new cooperation between public and private interests … and constructive proposals for concrete action,” for conservation.

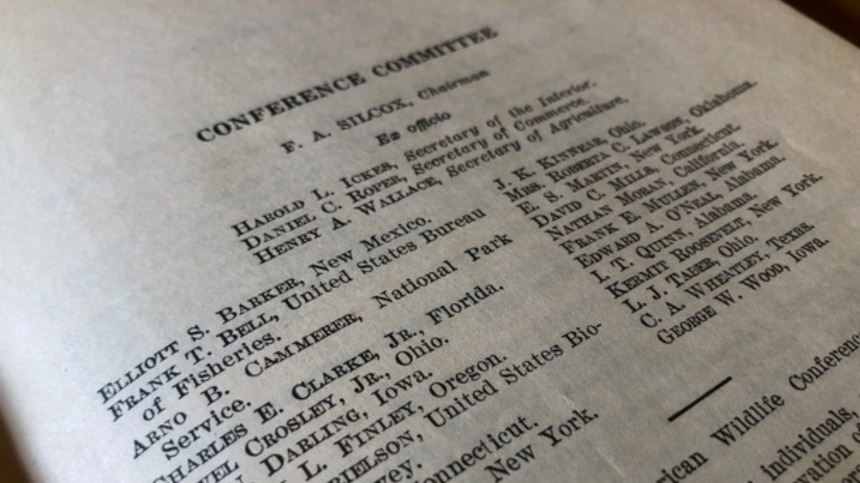

That third page lists the names and affiliations of the 22-member conference committee who convened representatives from a multitude of interests. J.K. Kinnear represented the angling industry as president of the Association of Fishing Tackle Manufacturers, and David Martin, the National Association of the Fur Industry. Others are long remembered in sculpture and place names.

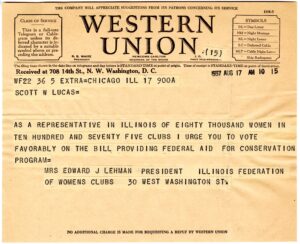

Roberta Lawson, national president of the General Federation of Women’s Clubs is memorialized in bronze in the American Indian Hall of Fame. Lawson was a member of the Delaware Tribe. Women’s organizations had ardent interests in conservation and clubs in Illinois under the federation proved pivotal in passing Pittman-Robertson. Lawson spoke at the conference on the need to educate the young in conservation and of the spiritual and economic values of hunting and fishing.

Ding Darling National Wildlife Refuge honors the work of political satirist Jay Darling who worked with a nascent Wildlife Management Institute and conceived the 40 cooperative fish and wildlife research units that exist today at colleges in 38 states. They are training grounds for future biologists—many of whom conduct research funded by the taxes paid under Pittman-Robertson or Dingell-Johnson.

Industrialist Powel Crosley, inventor, car manufacturer, and pioneer radio broadcaster, owner of the Cincinnati Reds—and ardent outdoorsman—teamed with Walter Chrysler to incorporate the American Wildlife Institute in 1935, the antecedent of the Wildlife Management Institute. His former Indiana farm is today’s Crosley Fish & Wildlife Area, managed by the Indiana Department of Natural Resources via Pittman-Robertson and Dingell Johnson funding where one can fish and hunt and train bird dogs.

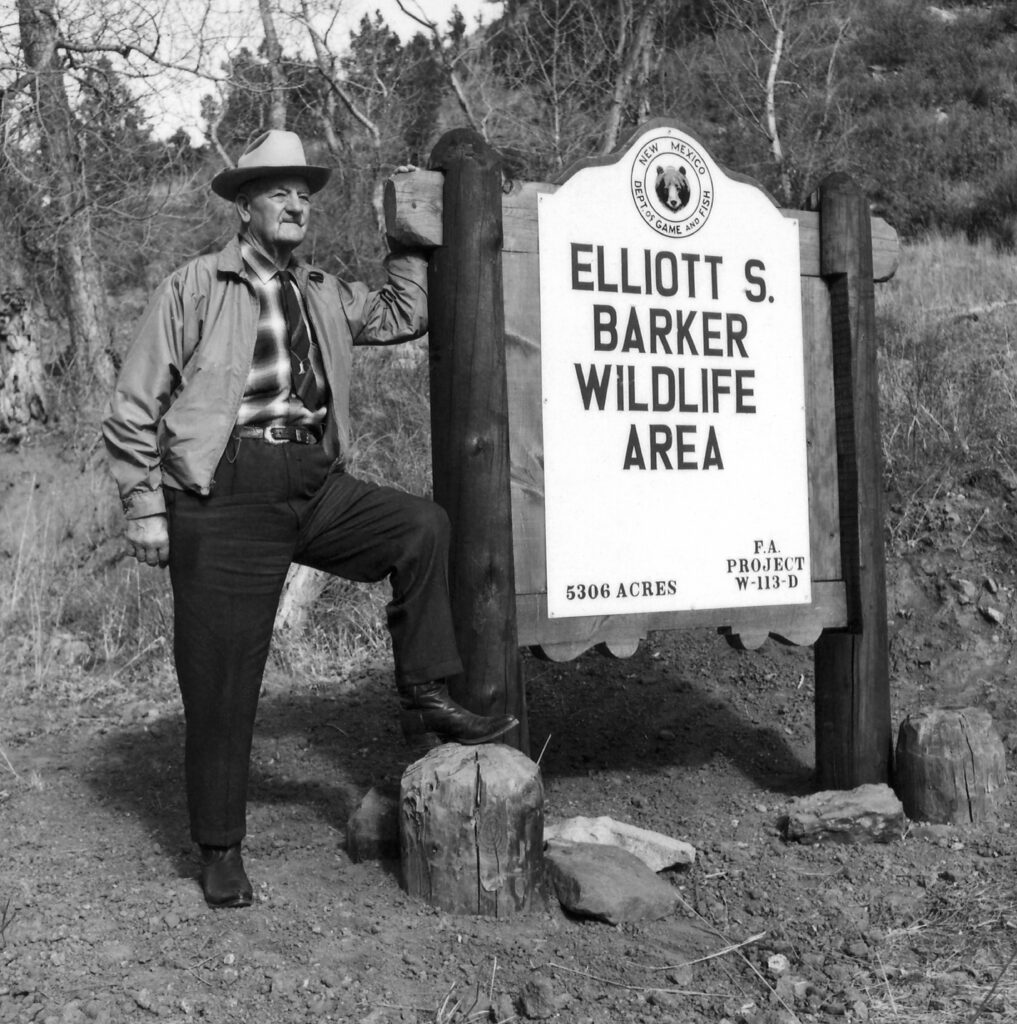

Elliot Barker came of age on a ranch at the turn of the 20th century in New Mexico’s Sangre de Cristo Mountains where mule deer, mountain lions and Rio Grande cutthroat trout captured his mind. He labored as a U.S. Forest Service ranger under Aldo Leopold. Barker became the Director of the New Mexico Department of Game and Fish in 1931—a position he held for 22 years. He had a hand in saving a badly burned bear we came to know as Smokey, and published eight books on conservation and the outdoors. Barker embraced fish culture in his tenure. Lisboa State Fish Hatchery on the Pecos River near his natal forest is presently under renovation through funds acquired from Dingell-Johnson. Its staff will wade chest-deep into Rio Grande cutthroat conservation. The New Mexico Department of Game and Fish named the 5,400-acre Elliot Barker Wildlife Management Area in his honor in 1966, acquired and managed for elk and mule deer via Pittman-Robertson dollars.

Wildlife and Sport Fish Restoration dollars today are quite substantial. In 2022, the territory and state fish and wildlife management agencies received $1.1 billion for Wildlife Restoration and $399 million Sport Fish Restoration. These are more than just numbers—these funds derived from commerce pay for scientific fish and wildlife management, research, land purchases, fishing and hunting and boating access, and hunter and angler education.

I have to think that Lawson and Darling, Crosley and Barker and all of their contemporaries would be pleased with the outcomes of their 1936 meeting. FDR’s desire for cooperation between public and private interests and proposals for concrete action, achieved. Pittman-Robertson and Dingell-Johnson run in the American grain. The past is only prolog. There is more to be done as spelled out in state wildlife action plans, and I appreciate the attention Congress has given this issue through their consideration of Recovering America’s Wildlife Act. The future is ours to make.

–Paul Rauch is the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service’s Assistant Director, overseeing the Wildlife and Sport Fish Restoration program in Washington, D.C. See Partner with a Payer to learn more.